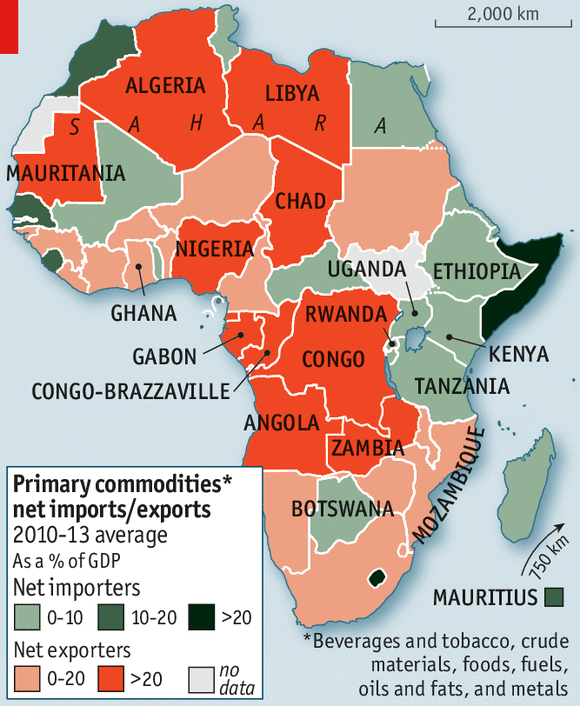

FOR decades commodity prices have shaped Africa’s economic growth. The continent is home to a third of the planet’s mineral reserves, a tenth of the oil and it produces two-thirds of the diamonds. Little wonder then that, as a rule, when prices for natural resources and export crops have been high, growth has been good; when they have dipped, so has the continent’s economy (see chart 1).

Over the past decade Africa was among the world’s fastest-growing continents—its average annual rate was more than 5%—buoyed in part by improved governance and economic reforms. Commodity prices were also high. In previous cycles African economies have crashed when the prices of minerals, oil and other commodities have fallen. In 1998-99, during an oil-price fall, Nigeria’s naira lost 80% of its value. African currencies again took a beating during a period of turmoil in commodity markets in 2009.

Since last year the price of oil has fallen by half and many metals such as copper and iron ore have also dropped sharply. With commodity prices plunging, will the usual pattern repeat itself?

In some economies large drops in commodity prices have led to currency falls. At least ten African currencies dropped by more than 10% in 2014. But there have been few catastrophic depreciations. This suggests that investors do not see lower commodity prices as a kiss of death. Ghana’s currency, the cedi, was the continent’s worst-performing currency in 2014, having lost 26% against the dollar. But it tumbled not because investors fret about the impact of lower commodity prices. In fact, Ghana is by African standards not especially commodity-dependent (see map). Rather, it has in recent years run a lax fiscal policy. In 2013 its budget deficit hit 10% of GDP.

The mall, not the mine

One reason currencies have been robust may be because economic growth is starting to come from other places. Manufacturing output in the continent is expanding as quickly as the rest of the economy. Growth is even faster in services, which expanded at an average rate of 2.6% per person across Africa between 1996 and 2011. Tourism, in particular, has boomed: the number of foreign visitors doubled and receipts tripled between 2000 and 2012. Many countries, including Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Mozambique and Nigeria, have recently revised their estimates of GDP to account for their growing non-resource sectors.

Despite falling commodity prices, the outlook also seems favourable. Wonks at the World Bank reckon that Sub-Saharan Africa’s economy will expand by about 5% this year. Telecommunications, transportation and finance are all expected to spur economic growth.

What explains Africa’s increasing economic diversification? A big pickup in investment helps. That has arisen partly because governments have worked hard to make life better for investors. The World Bank’s annual “Doing Business” report revealed that in 2013/14 sub-Saharan Africa did more to improve regulation than any other region. Mauritius is 28th on the bank’s list of the easiest places to do business. Rwanda, which 20 years ago suffered a terrible genocide, is now deemed friendlier to investors than Italy.

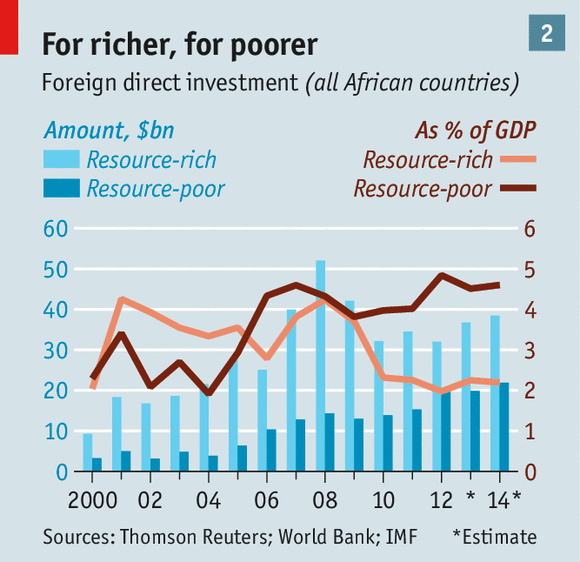

After two decades of poor performance, Africa’s total investment as a percentage of GDP increased after 2000. Foreign direct investment (FDI) into Africa rose by 5% in 2012 and 10% in 2013, despite global stagnation.

Ten years ago almost all FDI went to resource-rich African economies; resource-poor economies received very little (see chart 2). Resource-rich countries still receive more FDI in absolute terms; but resource-poor economies outpace them when investment is measured as a share of GDP. Foreign investors from other African countries are especially keen on non-commodity industries: nearly a third of their investments are in financial services.

The most resource-intensive economies are working hard to diversify. For the past three years growth in Nigeria, Africa’s biggest economy, has exceeded 5%. You might think its growth is being powered by oil exports. Nigeria has Africa’s second-largest reserves, it is the fifth-largest exporter and, according to the IMF, oil accounts for 95% of all exports. But in recent years the Nigerian oil industry has stagnated. Growth has instead come from things like mobile phones, construction and banks. Services now represent 60% of GDP.

Angola is similar. It is Africa’s second-largest oil producer and the stuff makes up the vast majority of exports. But its 5.1% expansion in 2013 came mainly from things such as manufacturing and construction. In 2013 fishing expanded by 10%, and agriculture by 9%. About a third of government revenue now comes from non-oil sources, compared with almost nothing a decade ago, economists at Standard Bank reckon.

In Botswana the percentage of GDP made up by the mining and quarrying of goodies like diamonds, gold and copper has fallen from 46% in 2006 to 35% in 2011, according to the “African Economic Outlook”. Other countries that are successfully diversifying are Rwanda—which has thriving banks and business-services firms—and Zambia, which although still copper-dependent has posted growth of 12% a year in financial services. Congo-Brazzaville, where oil makes up 80% of exports, is seeing rapid growth in construction and transport. That may be further fuelled by the All-Africa Games, which are to be held this year in the capital, Brazzaville.

Better fiscal policy also plays an important role. Commodity markets are volatile; government spending smooths out the booms and busts. Until a few years ago, nearly all African economies spent freely when their economies were hot, only to rein in spending when things cooled down. That is the opposite of what most economists would advise a finance minister to do. But in recent years, according to a report from the World Bank published on January 7th, fiscal policies in many African countries have become more sensible. These days a fair number of African economies save money during the good times, in order to spend it in the bad ones.

There is still a long way to go. Africa is still the continent most dependent on commodity exports. Countries such as Tanzania and Nigeria want to develop giant gasfields which, while boosting the economy in the short term, could tie them more closely to commodity cycles. Some worry that investment in infrastructure will fall as mining companies retrench.

Even so, there is reason to think the “resource curse” is losing its power. Despite turmoil in commodity markets, Africa is still one of the world’s fastest-growing regions. With better education systems, investment in infrastructure and sensible regulatory reforms, the continent could completely break the spell that has held it back so often in the past.